To be a College member is to be a traveler. In this section, contributors Diana Baron, Joshua Levy, Mauricio Urrutia V., Jose Manuel Matte, Emily Halpern, Sarah Gibbs, Frances Allen, Debayan Chatterjee, Rohit Lahoti, and Daniel Linde offer stories from homelands and foreign lands.

The Offices of Joy

by Diana Baron

“The offices of Joy are closed for the day,

Please come back on a weekday.

Today you should be at home,

Today you should not be alone.

Oh, that is the problem?

Well, sir, you’re in the right place,

Joy has been able to help countless

But unfortunately he won’t work for less.

You see, he’s not union,

Yes, Joy needs to pay his rent

So he works extra hard tomorrow

But today he cannot see your sorrow.

You see, he knows he’s wanted

Joy knows that many seek,

So he sets the terms of the gift

Tomorrow he’ll heal all rifts.

Well, sir, if you want to shout

I could call Anger and Pain

I am sure they will come today

They only seek a reason to hurray.

What is it you say sir?

Tomorrow the afterlife awaits?

Oh, I wish you hadn’t said that,

For now I have to call Fear.

I don’t like it when she comes

Near these premises,

Dark and turbid, it’s as if she fills

All the cracks in Joy’s estate –

It takes us hours to clean after she leaves.

Here she comes, sir, may peace be with you

After all, I don’t think Joy will see you.

You see, Joy prefers to keep a positive space

And you seem like you don’t have any

Positivity left.”

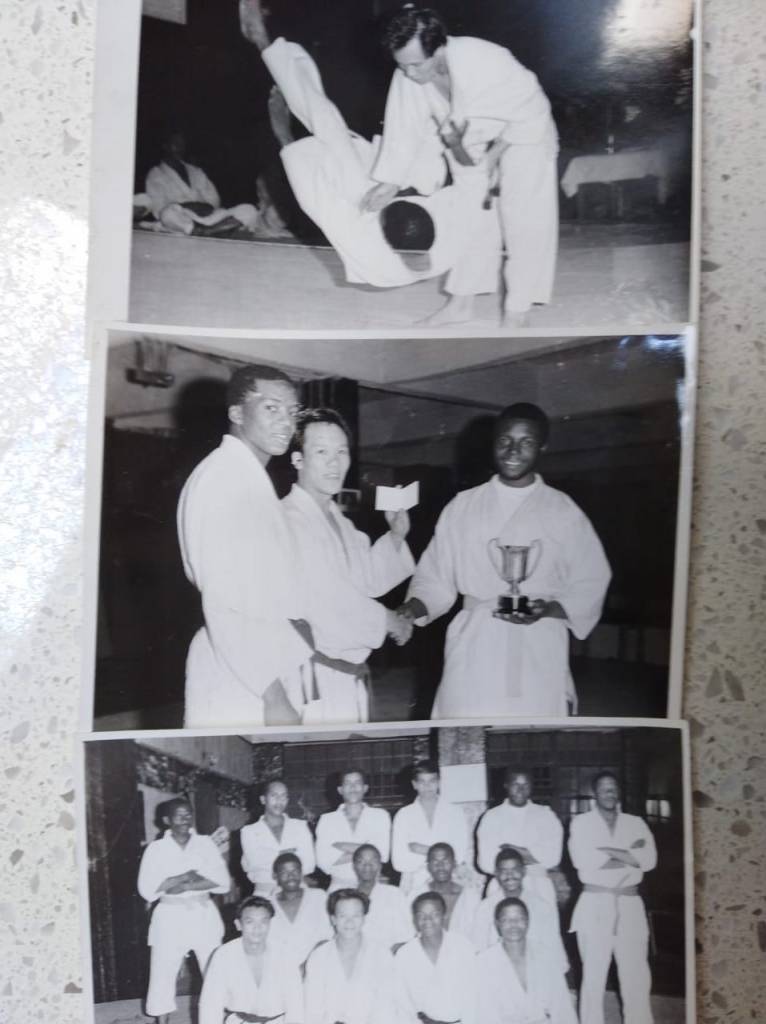

Of Protest and Challenge Matches – George Lai Thom and the Emergence of Judo in Apartheid South Africa

by Daniel Linde

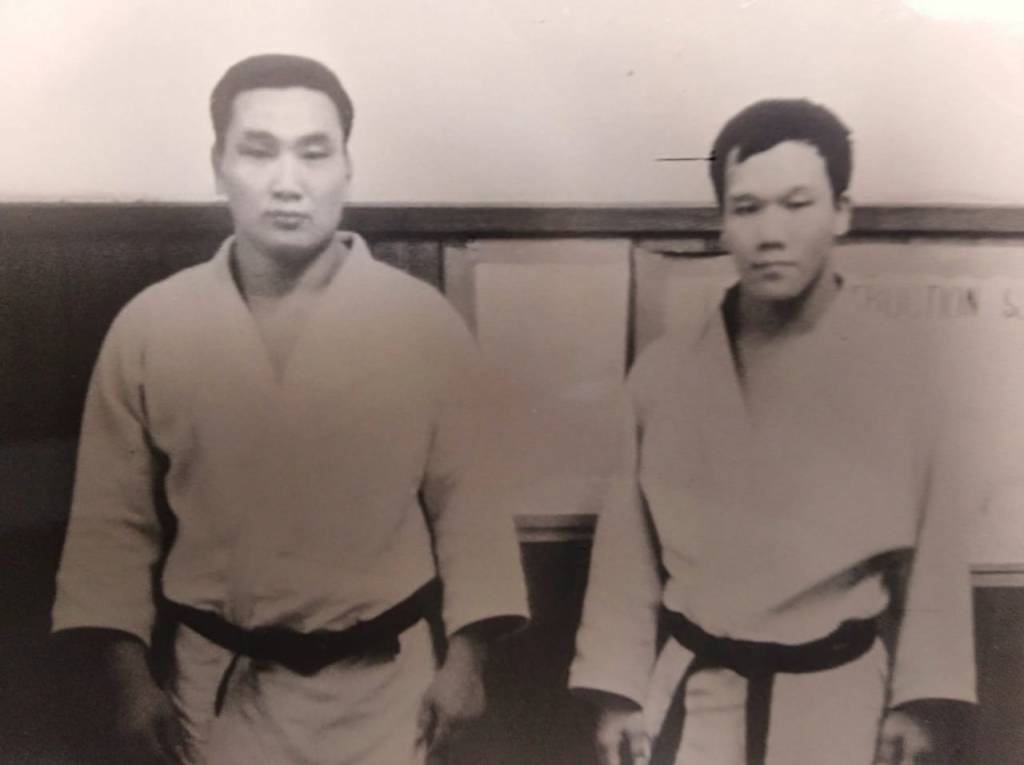

Lai Thom with Isao Inokuma 1964 Kodokan

George Lai Thom’s life in sport would make for a combination of martial arts flick and political docudrama. Born in Johannesburg in 1942, Lai Thom grew up in Newclare, just 2 kilometres from Sophiatown, the suburb famous as a symbol of black culture and resistance to Apartheid. His father was Cantonese. He was the youngest of 7 siblings.

As a teenager, Lai Thom regularly worked out with his sister’s boyfriend Ernest. Ernest was learning judo and, along with weight training, he would pass on his burgeoning knowledge to a group of young men at weekly sessions in Johannesburg’s Chinatown. On one afternoon in 1957, Ernest brought along his own instructor, Duggie Baggot, to teach the class.

Baggot was an imposing figure. A mammoth of a man, he was building a reputation on the South African bodybuilding scene, where he trained out of the gym run by Arnold Schwarzenegger’s mentor, Reg Park. Despite his appearance, Baggot’s athletic interests went beyond the weight room. From the mid 1950s he had studied judo under Jack Robinson, a British wrestler and judoka who, along with his sons, pioneered the sport (and later karate) in South Africa. Under the tutelage of the Robinsons, Baggot had learned judo in earnest and, by the early 70s, he would be graded to fourth degree black belt.

Speaking with me in September 2018, Lai Thom recalled his first impression of Duggie Baggot. Standing outside the weights gym in Chinatown, he was blown away. “I had never seen anyone as muscular as Duggie” Lai Thom recalled. “He seemed like some kind of superman to me.. So I asked him to teach me judo”.

Under Baggot’s guidance, Lai Thom threw himself into the sport. He spent hours each day breaking falls on the hard judo canvass, perfecting his techniques at Park’s gym cum dojo in the days before the cushioned tatami (judo mats) were readily available in South Africa.

All of Reg Park’s gym instructors were white. “There was a black cleaner”, Lai Thom told me, “and he was permitted to use the weights, but only after hours”. After Apartheid’s demise, Reg Park’s son made a promotional video claiming that his father had been the first person in Johannesburg to allow black people to train at his gym. A frustrated sarcasm permeated Lai Thom’s voice: “I see this everywhere..” he sighed.. “Nobody supported Apartheid. Mandela was everyone’s hero”. And those who systematically denied black and coloured people their freedom and dignity, in sport, work and love? “You can’t find them”.

George and Wilcox

Lai Thom climbed the ranks in Robinson judo, earning his black belt and developing a strong faith in the effectiveness of his training. That conviction was shaken sometime around 1961, when a group of German judokas arrived on the Johannesburg scene. Not one to shy away from a fight, or from the prospect of one of his sons fighting for the honour of the family and their arts, Jack Robinson issued a challenge: he volunteered his youngest son Norman and another top student to take on the Germans.

The matches took place at the dojo of Sebastian Hawkins, then chair of Karate South Africa, who had employed the German immigrants to teach at his school. “A big crowd came along”, Lai Thom remembered. Jack Robinson’s son Norman was much heavier than his German opponent, Werner Zeltinger, and had a higher degree black belt ranking. Despite this, the match was close. In the early exchanges, the German fighter threw his bigger opponent to the ground, but the throw scored no points, as Robinson had fallen out of bounds. Though Norman Robinson eventually won out, Lai Thom was astounded at how well the smaller and lower ranked man had performed.

In the second challenge match, a top Robinson black belt, Imre Andros, took on Gunter Herman, a German judoka with the much lesser rank of green belt. “Gunter proceeded to throw Imre around, five or six times”, Lai Thom told me. “Up till that time, I had never seen throws like that. It blew my mind”.

Understandably disillusioned, Lai Thom began training under Zeltinger. Though they held the same rank, Lai Thom believes that Zeltinger was the far superior fighter. “He threw me around like a baby!”.

Lai Thom told Zeltinger he was uncomfortable wearing his black belt in his new dojo. He felt his abilities did not justify the rank. Zeltinger pushed back. Showing respect for the Robinson’s grade, Zeltinger told Lai Thom to continue wearing his belt, rightly predicting that the young man would soon enough close the skill gap.

Despite the outcome of the challenge matches, and his move over to the German school, George Lai Thom still idolised Duggie Baggot. Though he had moved away from the Robinson judo school, he and Baggot, who would go on to marry one of Jack Robinson’s daughters, continued to train together. Lai Thom’s prowess in the sport grew. Through his exposure to the German school, his continued training with Baggot, and visits to Japan to train at the international headquarters of judo, the Kodokan, George Lai Thom developed into one of the leading practitioners of the sport in South Africa. But his hopes of continuing to rise in the ranks in his country of birth would be dealt an irreparable blow, when the reality of Apartheid bigotry came to the fore.

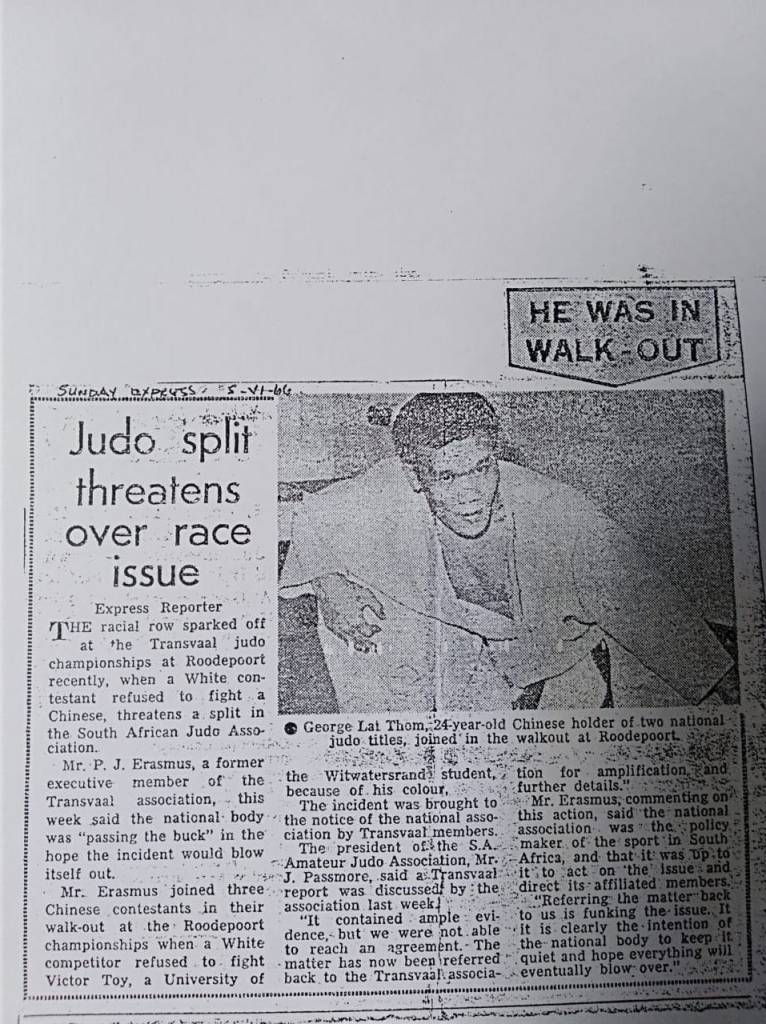

Until the 1966 provincial Judo championships in Roodepoort, practitioners of East Asian descent had avoided the exclusion that faced black South Africans. That was, until Victor Toy stepped up to compete. Although Lai Thom recalled it being Toy’s first tournament, an article from the time suggests that Toy, a 19 year old South African whose parents were Chinese, had competed at the provincial tournament the previous year, winning a title. Regardless, he would have had little sense that anything was untoward, as he took up his position and readied to bow to his opponent.

Toy’s counterpart was called to the competition floor three times, but never appeared. A commotion ensued between the officials. Whispers amongst the spectators reached the competitors. Toy’s opponent was refusing to fight. Toy was “coloured” in his white opponent’s eyes, and had no right to compete. When the officials’ discussion concluded, the referee raised his hand toward the empty mat space where Toy’s opponent should have stood, signalling victory for the white fighter. In the ordinary course of things, a competitor who refuses to fight forfeits. But this was no ordinary country. Toy had been disqualified.

“I knew trouble was coming at that tournament”, Lai Thom said, remembering the trauma of the incident some 52 years later. Officials had approached him in the change room before the fights had begun, asking whether he was Japanese or Chinese. The Japanese had been granted so-called “honourary white” status by the Apartheid government at the time, and were in no danger of exclusion from competition. The Chinese had no such privilege. Lai Thom refused to answer the question.

Rumours circulated that the racist refusal to fight Toy was inspired by a disdain for the Chinese practitioners’ practice of training alongside black judoka. It was particularly well known that Lai Thom had withstood pressure to draw a colour line at his dojo in Johannesburg. He was a friend and training partner of Wilcox Mqulo – the champion of South Africa’s segregated black judo division, and the only black South African at that time to hold a black belt. Unbeknownst to almost everyone but Lai Thom, Mqulo had secretly watched the championships that day. Barred from attendance by virtue of his skin colour, he peered through a window as Lai Thom led a walk-out in protest of Toy’s treatment. Several white spectators, including at least one tournament official, left with Lai Thom.

In the wake of the walk-out, Chinese judoka were barred from participating in the national championships in Cape Town. Lai Thom, who had won gold the previous year in both the 165 pound and open weight divisions, could not defend his titles.

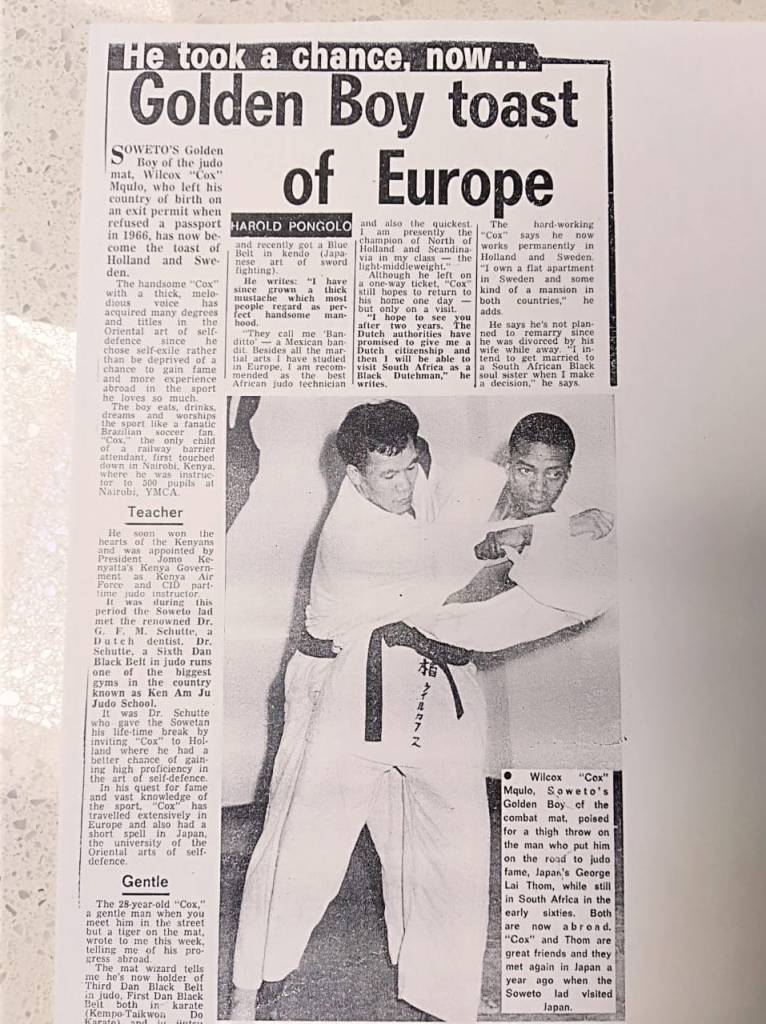

Less than a year after suffering the indignity of watching a judo competition through a window – one in which he no doubt would have bested many of the competitors had he been given the chance – Wilcox Mqulo left South Africa on an exit permit to Kenya. From there he fled to Holland, taking up an instructing post at a well-known judo school.

Seeing no future in the country, George Lai Thom prepared to leave for Japan to train at the Kodokan, eventually settling in Canada. The Roodepoort incident had made international news, with the world’s leading martial arts publication, Black Belt Magazine, running a story on Lai Thom’s role, with the headline “South Africa judo champion quits country over race dispute”. Lai Thom joined the political activities of the ANC, the then banned South African liberation movement. (Later, in the 80s, he taught judo and karate at an ANC school in Tanzania). Unable to practice his passion in his own country, Lai Thom continued to compete abroad. Seven years after the walk-out in Roodepoort, George Lai Thom was crowned grand champion of the 1973 Pacific Northwest Invitational Judo Championships in Washington, DC.

Walkout Article (Sunday Express)

George teaching a group of black students

WHY I’M HERE

by Joshua Levy

after Jacqueline Berger

Because my mother was just a teen

in need of a summer job, and my father,

neck deep in law school,

asked her out as a distraction.

And because, years later, there was

little to do that Ottawa winter of ’79

but play Scrabble, experiment with recipes, and—

But it’s more complex than that.

I’m here because Jews were hated

so my father’s parents came to Canada,

danced jazz, and found a new raison d’être.

I’m here because my grandmother was 19

and in the ’50s that was plenty old to marry.

And because my grandfather tired of squeezing fruit

in his father’s fruit store, bought a hammer

and impressed his new boss with his mind.

That boss asked my grandfather

to deliver a package to his daughter’s house.

My grandmother answered the door, her hair down.

My grandfather was in a good mood that morning,

handsome, charming. The conditions

were right. Or, further back, to my

grandfather’s boss who fell in love

with two large eyes “so brown, so shiny”

I would later hear him say on tape

—but that were promised to another.

He was as competitive as he was romantic,

walking her to the neighbourhood

park, talking with his hands

and securing in this way the future.

The rest of the reasons are ridiculous.

Ships blew off course, harvests were reaped, and in war

the right people died and remarried.

The mulish defenders of fate are merely mulish.

Our family around the dining room table in May.

My father is cutting the braised brisket.

That used to be my grandfather’s job—he became

a tycoon and remembers none of it. My grandmother,

sitting beside him dressed in white,

is young enough that strangers ask if I’m her son.

We’ve been gathering here for years,

but I know it’s not forever.

For now, I praise the brisket, the salads, the gravy,

look out the window at the greying sky.

So many things went wrong

to make this right.

SEVEN YEARS

by Joshua Levy

Once, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,

I arrived all stubble and turtleneck,

weighed down in heavy black shoes,

and you waited with a steaming wax cup,

your blond hair a tangle of question marks.

I kept asking how your day was going

though I knew this drove you crazy,

but I didn’t know how to love back then.

Between Cezanne’s fruits and Miro’s doodles

we vowed to visit Emily Carr’s forest in B.C.

You said: “My mom will be a famous painter

once she’s dead. That’s how these things go.”

Today, I read an article about how we replace

every cell in our body every seven years,

which means, technically,

we have now never touched.

I’m not sure how I feel about this.

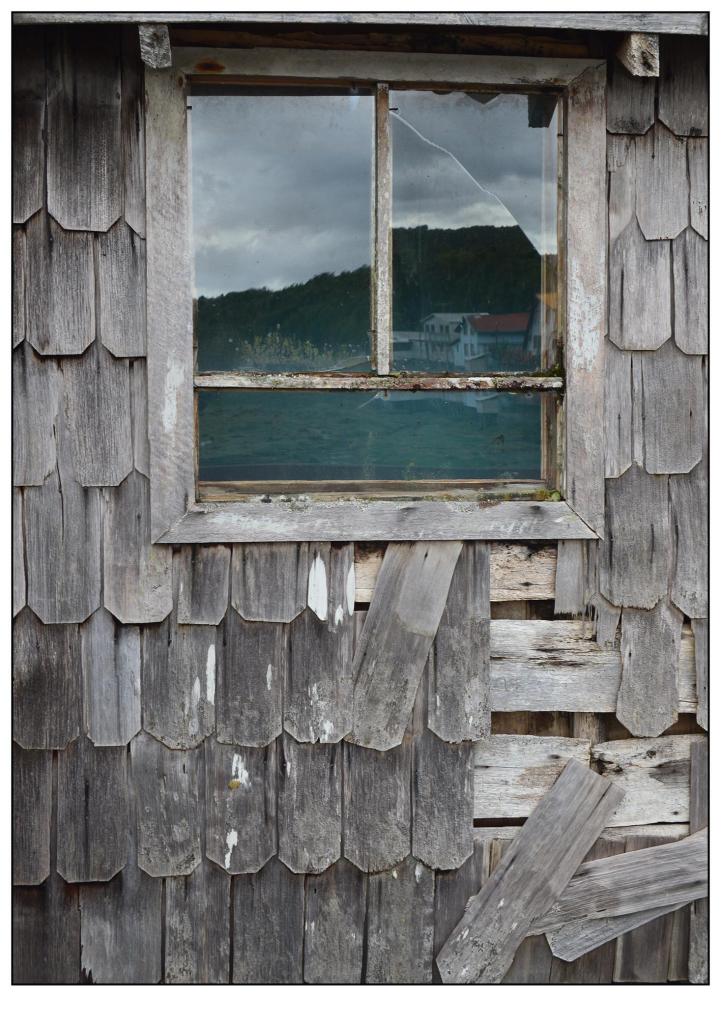

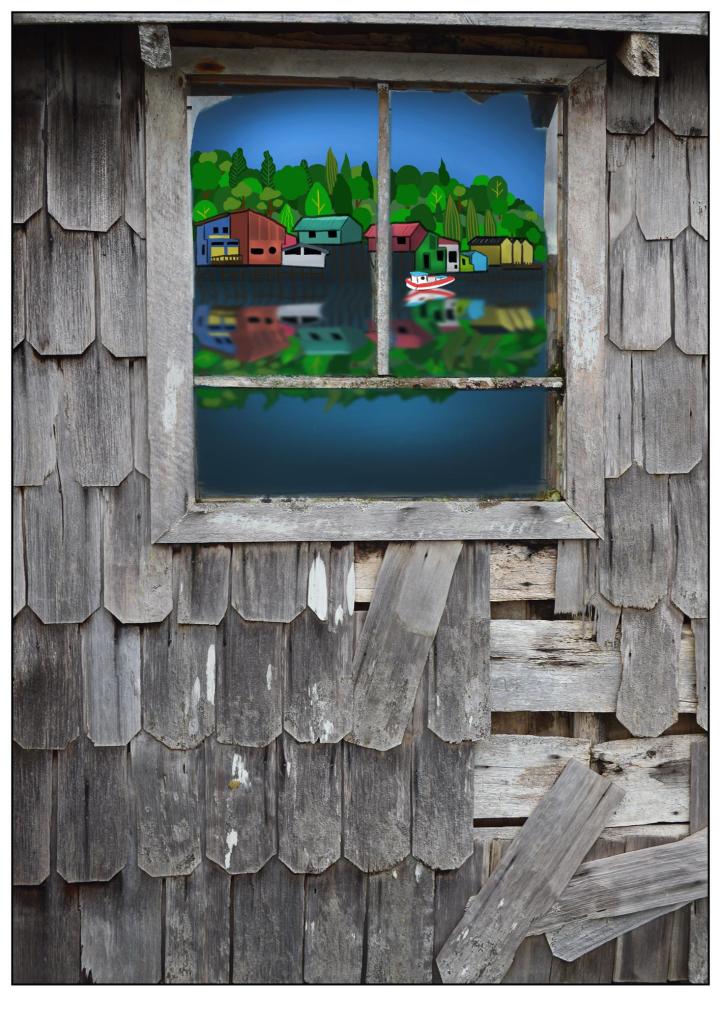

MAPPING

by Joshua Levy

[with Jose Manuel Matte. “Jaisalmer, India.” (2015)]

Under ribs

of arched

limestone

and stained-glass

angels, by

the muddy

mouth of

the Tagus River

Portugal buried

two supermen

in matching tombs,

side by side,

glazed in light.

Vasco da Gama

1469–1524

Sailor

Luís de Camões

1524–1580

Poet

Back-to-back

life spans—as if

the sailor needed

the poet to map

shores ships

can’t grasp.

Emily Halpern. Biscuits as Cultural Memory (https://www.instagram.com/bakerandbardbaking/)

Mick

by Sarah Gibbs

It’s a common name.

My parents are Irish. I know it’s a common name.

It’s got a “from the village” feel.

It’s got the pub in it.

Like someone calling to you over a stone wall while they’re getting the hay in.

That’s in it.

So is your man leaning over the half-door.

My mother said they’d never had a half-door. Those belonged to poor people, gurriers,

people who’d left their “th” ’s in a ditch somewhere.

She was angry, I think, from being called that name often, when what someone meant was

“Get Out.”

No Dogs or Irish.

My brothers and I, our names are untraceable,

no rock called “The Old Country” to push up a hill.

There must have been a chorus of

“God bless ye, Mick”

on the quays in Cork, Donegal.

For it’s got the leaving in it too,

the mothers in the houses that echo:

a country of the old. The children are made out of paper.

Now the whole world is planted with them, by them,

and the name’s got new things in it, other attachments.

The clang of boots on iron girders from the steel walkers building the Empire State, swinging over

Nothingness feet that had touched ground in the green fields.

A nothingness building itself.

It’s got a whiff of the sheep dip in it, tang of red clay from the largest farms in New South Wales.

And there’s frost on its edges. In it now is a homestead in a winter that doesn’t end,

when the snow is four directions of blankness and the sky is so big it’s a weight.

I didn’t know him.

Maybe he lived and died in the house where he was born, jumper on and feet in the fender,

having nothing of leave-taking,

of fire or ice or walking on air.

I didn’t know him.

But ‘tis a good name.

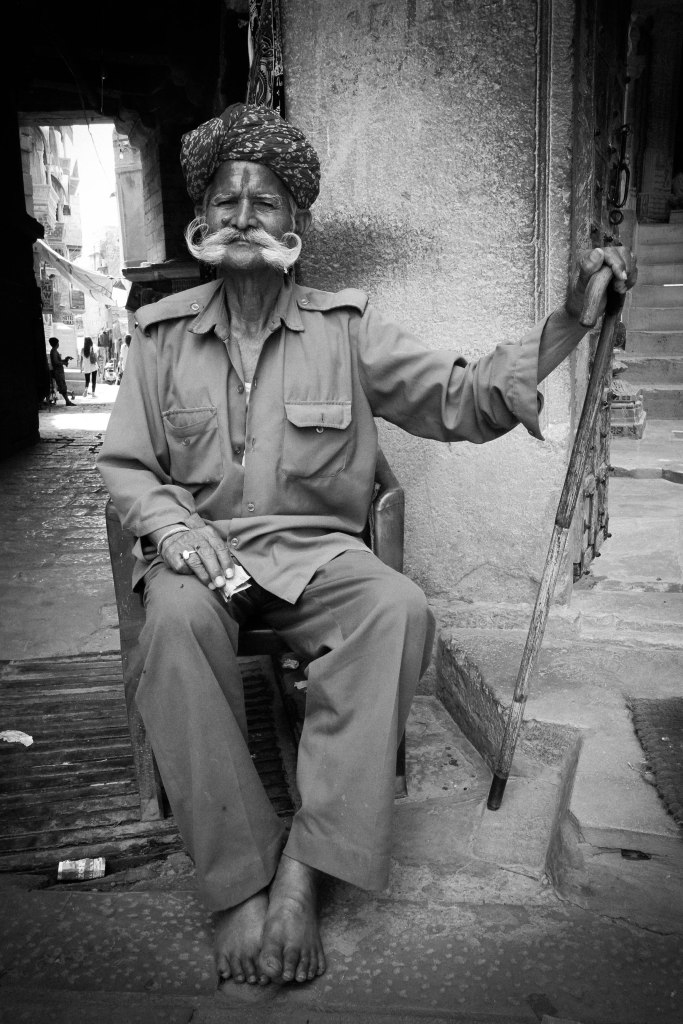

Streets: Of the people, by the people, for the people!

by Rohit Lahoti

One of my fondest remembrances while reading Jane Jacobs is when she talks about the uses of streets and the sidewalks, and how they “bring together people who do not know each other in an intimate, private social fashion and in most cases do not care to know each other in that fashion”.

This photo essay is an attempt to document some of such street-play that I have witnessed during different points in time—particularly in Mumbai, Varanasi, Ahmedabad, Pushkar, Jaipur, Bikaner, Thane, Abu Road, and Jaisalmer.

When I observe that woman’s body language as she walks on the street in the rural part of Abu Road or the metal separation between the street and the new construction in Mumbai which is used as a selling spot by the vendors, it is evident how the behaviour of any of these streets is defined by the people and the social context of the place. They also manifest the idea of ‘public place’ in an organic manner, unlike the defined ones in the European piazzas!

Streets of a place also gives visibility to various layers and what is happening in those layers. I saw this prominently happening in the old part of Jaipur, early in the morning, when the city-life was steadily unfolding. In the photograph there, one can see the distinctions we have in our society. On one hand, the owner of the commercial space is praying, on the other hand, another layer in the foreground shows the lady doing her daily cleaning work.

Streets have a quality of surprising people. In the quaint city of Pushkar, where the Pushkar Lake defines its spatiality, streets run concentrically and cutting through them to reach the lake. In the photograph, one can see the transition from the street towards the lake but in a piecemeal manner.

Streets are accommodative of people while Indian streets are accommodative of animals as well. This was prominently evident during my time in Varanasi when I had to stop multiple times while moving through the labyrinth in order to provide the space for cows to pass. In an early morning photograph there, one can see the shared nature of the alley along with the house extensions—also called otlas—used not only for people to sit but also to keep the milk tumblers. While these

extensions, where the public-ness and the private-ness of a space is diffused, are also used forcelebrations—as seen in the photograph in the old part of Jaisalmer.

Streets, when not governed or defined to the point that they become exclusive, metamorphose with time. The stretch between Bhadra Fort and Teen Darwaza in Ahmedabad is a specimen of this characteristic. I visited this place on a Sunday and the variety of activities that were happening—with the kind of ephemeral spaces that were engendered at the same time—gave a peculiar vibrancy to this milieu of Old Ahmedabad. It was like a theatre where every element had its own significance in giving the space its identity. Analogous to this was also a street in Thane which I captured on the festival of Gudi Padwa—when people come and reclaim the streets in their own ways.

Inspired from Balkrishna Doshi’s comparison of architecture to a living organism, I believe the same for cities. The streets, then, become the arteries that run them—certainly in ways more than one!

Jose Manuel Matte. “Isla del Sol, Bolivia.” (2012)

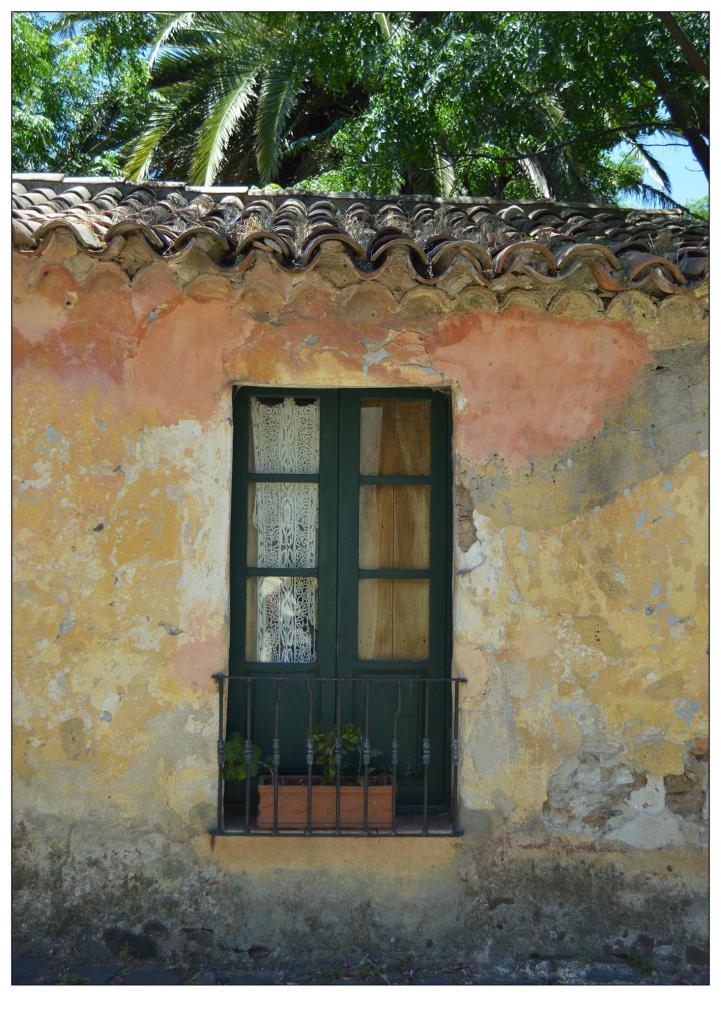

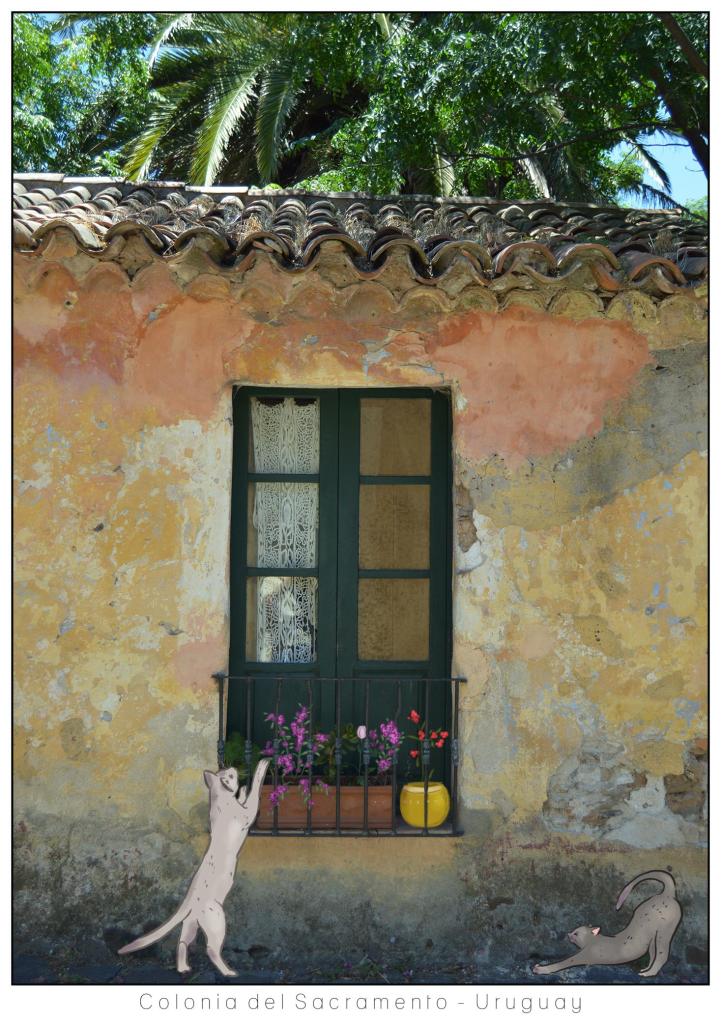

Sacramento – Uruguay”

Sacramento – Uruguay”