College members were moved (literally and figuratively) by the TFL. Contributors Frances Allen, Nicholas Rawhani, Katerina Zacharopoulou, and Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún reflect on London’s circulatory system.

Inspired by the writings or Marc Augé:

“Transgressed or not, the law of the metro inscribes the individual itinerary into the comfort of collective morality and in that way it is exemplary of what might be called the ritual paradox: it is always lived individually and subjectively; only individual itineraries give it a reality, and yet it is eminently social, the same for everyone, conferring on each person this minimum collective identity through which a community is defined”

I Am in an Underground Car

by Katerina Zacharopoulou

I am in an underground car.

I know that the first sentence in every story presupposes a past. In this case my identity, all the general information about myself and my background, but also more specific information, such as to which line this car belongs, if I‘m sitting or standing, where I’m going and where I’m coming from, what time it is. I won’t talk about any of these presuppositions. Not because they don’t matter, but because I don’t have any clue about them. I am just the protagonist of a story, and I have every right to be in an underground car without knowing anything else about it.

I am in an underground car. The car is moving, on this verge between two stops. In the windows I can see my reflection and the reflection of everything inside the car (don’t ask me what is inside the car; I don’t know). Outside there is only darkness, interrupted now and then by a strong light, so strong that its result is the same as that of darkness; I can’t see anything. But I can hear. I can hear the noise of the car’s movement, which is at times extremely loud, at times just very loud. I become aware of being under the ground. Under-ground. Underground. The darkness and the noises scare me. The underground scares me.

The car is still moving, on this verge between two stops. I am trying to hold on to something, find a periodicity in the lights or the noises, to make this anxiously indeterminable span between two stable things, two stations, go away quicker, or, at least, become more tolerable. I don’t achieve anything. I don’t notice even the slightest lowering of speed, the hint of an arrival at a station. I don’t know how long this will last, but I know that at some point it will end, just like a story does, because a train starts from somewhere and arrives somewhere, that’s why it exists, and if I told anyone I believed that this transitory state wouldn’t finish, then I would for sure be considered insane. But I still don’t know when it will finish, and the longer it continues, the longer the time that it hasn’t finished yet gets. Just as grains of sand fall when an hourglass is turned over, and form a pile out of nothing, with every second that passes, with every grain that falls, the mad suspicion that this will never stop slowly becomes a not at all unreasonable certainty.

I am just the protagonist of a story, and I have every right to be in an underground car without knowing anything else about it. What if the car never stops?

Victorian Line Hearing Aid

by Nicholas Rawhani

I held on tight

to the laminated blue handle

of the 22:04 Victoria Line train

to Stockwell,

packed so full of people,

bumping up and down,

watching the dirty

blackened

finger

nails

of the violinist as he

played along

to the song

howling out of the old amplifier

he’d lugged aboard.

His finger-tips were hard

and articulate

and grimey

and his silver hair danced knottedly

to the boogy-woogy

rhythm

of his song,

all unharmonized

by the sharpquick whines of the

metal lines

that scraped beneath our feet,

the droning feedback of someone’s

hearing-aid

and the velvet black echo

of the tunnel

we were hurtling through

all together.

His skin looked like it had been

covered

by the soot of a thousand

chimneys

ground-down and rubbed in

and then wiped away

by a dry old cloth.

i didn’t much like the music, but I gave him

85p

so that his nails could be clean.

He didn’t look up

until he

finished his song

and we started clapping a bit –

me

and the man with the

hearing-aid.

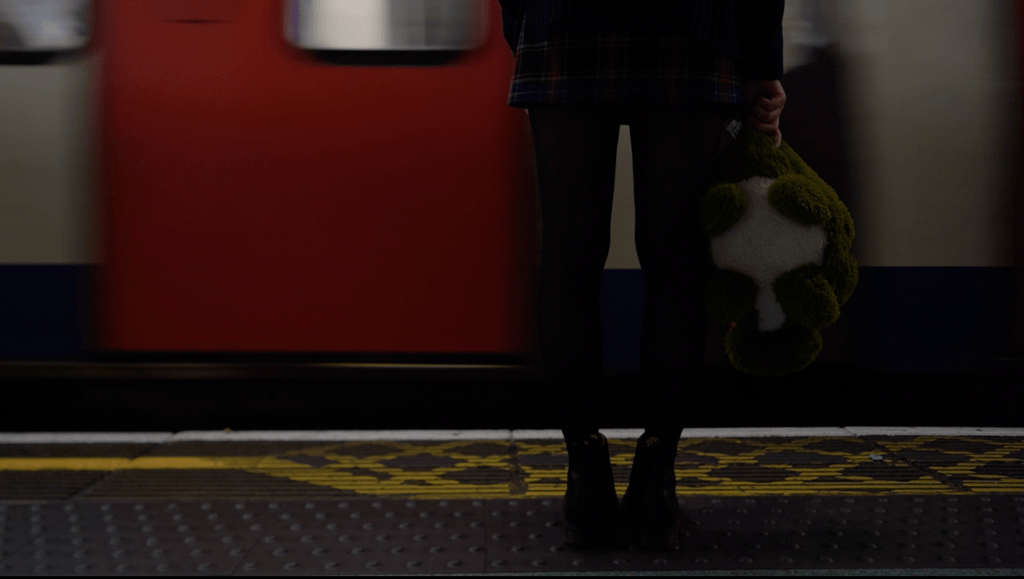

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún. “Stranger by the Train.”

Vincent the Blind

by Nicholas Rawhani

The drizzle in London has definitely gone to finishing school.

Polite and reserved, indirect,

icy-cold and entirely unsubstantial – you are unsure what the drizzle is saying

and then all at once you find yourself completely soaked.

I was at Liverpool Street Station waiting for the 48 bus to take me back to

Hackney, swimming in a crowd of people using poles and umbrellas and

coats and plastic bags to avoid the polite and entirely un-welcomed drizzle conversation.

In South Africa, people smile and greet. In London, the only people who greet back

are the African Aunties, whose smiles give me a little bit of the sunshine I’m used to.

I routinely play “Sweet and Sour” in London.

It’s a game of social risk and daring. Simply put, you greet people or smile at them as you go past and if they

return the greeting or the smile, or even nod (one must adjust one’s expectations) then they are “Sweet” otherwise

they are banished to the “Sour” list forever (or at least until the unlikely event that you happen to pass them again

in a metropolis of 10 million people and they happen to

be in a better mood).

I was in the process of being drizzled on and tallying up my morning’s Sweet and Sour scores when I felt a tap on my shin.

A respectable, light tap, as though someone had a stick and was using it to gently rub a stain onto the bottom of my trousers.

I took my earphones out and turned around to see a short, roundish man speaking to me while looking down at the ground.

He was in the middle of a sentence by the time my earphones were out,

” – and then I’ll just get on”,

“excuse me?”

he repeated himself, “Mate, le-lemme me know when the-the 48 bus comes and then I’ll just get on.”

He spoke quick, in a low mumbly stutter, sort of using his mouth more for buzzing than speaking.

“No worries,” I said still trying to figure out what he had just asked me.

“I’m actually taking the 48 too,” I said once I had caught up with the situation “so we can get on together”.

The drizzle had finally stopped and everyone was somewhat relieved and drying off. The 344 to Clapham Junction came by

and he did a little inquisitive flick of his head. “That’s the 344,” I said. “What is your name by the way? I’m Nic”

“David,” He said and gave me his hand to shake.

David took out his phone, a burner, and typed on its keys while looking up in the air and swaying a little bit. “Zero” the phone announced, “Seven-Seven…” and so it continued.

Then he put the phone to his ear, “Hello, yes, thi-this is Vincent, case number 20412, I’m calling because you still haven’t gotten back to me

about my request, and if this ta-takes much longer I’m go-going to have to complain..”

I imagined how difficult it must be for the person on the other end of the line to understand what he’s saying.

“I don’t want to have to call again.” He says as he puts the phone back into his pocket. The 48 bus pulls up and I tap him on the shoulder,

“This is the bus, David” I say.

He takes my arm and we step onto the bus, sitting right down in the front with me next to him.

“So wha-what’s your name then?”

“Nicholas”

“Alright”

We sat on the bus for a little while, and I wasn’t really sure if my responsibilities to him had finished. He was still next to me, he seemed to be thinking very hard about something.

“Ni-Nic, could you take m-me for a sandwich?”

“Sure” I said. I had an extra half-hour, no rush. We got off at the next stop and he knew exactly where he wanted to go.

“Take my arm, right up there, y-yeah.” We went into an off-license where he asked me to grab him a packet of Cheese & Onion crisps, he took out a small plastic bag with money in it and gave some to the cashier. We went next door into a small cafe, where he was obviously a regular. I figured this had to be the case since the lady behind the counter seemed to understand the short buzz he made in her direction (which I assumed to be an order) and said “It’ll be ready in two minutes, go take a seat”.

He touched his watch and held it to his ear while looking up at the ceiling “Three-thirty-seven PM” it announced. “Wha-what colour is your shirt? You know I can see colours if th-they are close by.” He reached for his glass by touching gently in it’s direction and then putting his hand over its lip.

“It’s yellow. Shall i bring it forward?” He brought my sleeve close to his eye and then let out an approving “hm”.

Vincent was wearing a light-blue Little Britain T-Shirt with two characters, both looking sort of offish, and a large speech bubble coming from the mouth of one of them saying “I want that one”

“I like your shirt, its funny” I said. “Whi-Wh-Which one is it?” he asked.

Vincent’s sandwich came and told me a bit about how he has five siblings and about how they tried to rob him of his life-savings and how, since then, he feels lonely. Vincent tilted his ear to his watch as he pressed it, “Four-oh-nine PM” announced the watch.

After we left the store and walked along the street, I told Vincent I’d be happy to have a sandwich with him any time he’d like.

He didn’t reply to my offer and asked “Which street is this?”.

He said that he would go on from here alone, pushing the ball at the end of his cane right into the corner of the shop-fronts and sticking close to the walls of the buildings that lined the polite and grey, drizzly London streets.