Mecklenburgh Square is a source of endless inspiration to all who are lucky enough to call it home, even if only for a while. Contributors B. J. Rahn, Benjamin Gallup, Claire Hurley, Kólá Túbòsún, Chi-Yu Lee, and Cora Drozd offer glimpses of life in and around our haven at the heart of Bloomsbury.

Claire Hurley. “The Moon Inside Holy Cross Church”

SQUARE HAUNTING: Five Women, Freedom and London between the Wars

by B. J. Rahn

As a professional woman living in Mecklenburgh Square in ‘a room of my own’ for over 50 years, I was delighted to hear about Francesca Wade’s new book Square Haunting which celebrates five remarkable women who helped to shape, and were shaped by, the ethos of Bloomsbury between the two world wars. Although the book focuses on women who were both personally exceptional as well as emblematic of a particular era in which women were gaining independence, it also evokes life in Mecklenburgh Square as characteristic of wider Bloomsbury. One could argue that it was not Mecklenburgh Square per se but its location in Bloomsbury which fostered their aspirations. The title, taken from an entry in Virginia Woolf’s diary in April 1925, expresses her delight in exploring Bloomsbury: ‘I like this London life in early summer – the street sauntering & square haunting’.

What attracted women to Bloomsbury? ‘Early in the twentieth century, Bloomsbury was a byword for left-wing politics and modern culture’ (20). Its affordable housing offered freedom and autonomy to women as an alternative to conventional domestic life. And most of its denizens were artists, writers, intellectuals and professionals. Best known today are the three literary authors – Hilda Doolittle (‘HD’), Dorothy L. Sayers and Virginia Woolf. The fiction and poetry of these writers have remained in print but the same cannot be said for the more academic, theoretical and controversial work of Jane Ellen Harrison and Eileen Power.

Nonetheless in her day Harrison, the classical historian, translator and promoter of Russian polemicists, was a renowned and influential figure. According to Gilbert Murray she ‘was a pioneer who stimulated others to go past her’ and ‘her thinking changed history’ (328). Eileen Power, economic theorist and historian, ‘was well known as a public intellectual, her high standing exemplified by the popularity of her lectures and BBC broadcasts, her eminent position at the LSE and the international demand for her teaching’ (323). However, her reputation was subsequently overshadowed by the men who had worked with her, including her husband Munia Postan, with whom she developed a methodology of economic history – ‘a scientifically rigorous yet humane approach, applying economic concepts to history and making comparisons across time and place’ (324).

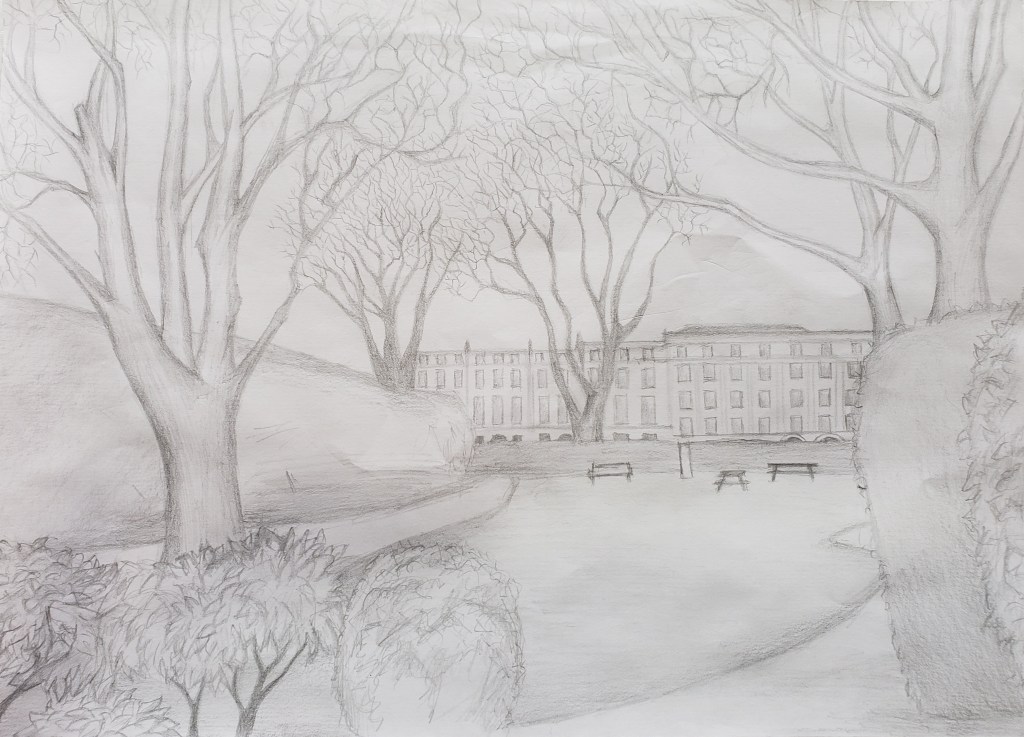

Benjamin Gallup. “Mecklenburgh Square – Winter.”

Achieving success during one’s lifetime is no guarantee of lasting reputation. Wade’s research was impeded by burned papers and vanished correspondence whose absence can bestow undue importance on information in surviving records (323). Though their periods of residence, professional endeavours and social circles seldom overlapped, life in Bloomsbury was a seminal matrix for them all, particularly for Virginia Woolf and Dorothy L. Sayers.

What they all shared were similar goals: ‘a determination to carve out new moulds for living – varied, multiple, complex, sometimes dangerous, yet always founded on a commitment to personal integrity and a deep desire for knowledge…knowledge of history and literature, knowledge of the wider world, and self-knowledge, no less difficult to obtain’ (337). ‘They were all interested in personal freedom, but were alert also to the ways in which their private struggles intersected with those of others, across place or time, race or class’ (30).

In this book Virginia Woolf’s influence extends beyond the choice of title and the chapter devoted to her life. Her spirit pervades the text like an éminence grise as Wade refers frequently to her perceptions, experiences, ambitions and philosophy throughout the framing chapters about Mecklenburgh Square and draws correspondences with the other women’s thoughts, feelings, principles, ambitions and behavior in chapters about them. Woolf’s feminist manifesto, ‘A Room of One’s Own’, prompted Wade to research the histories of the other female professionals she discusses. Her accounts are linked by the experience of each individual as she creates a new life in a room, or rooms, of her own amidst the stimulating, cosmopolitan milieu of Bloomsbury. Wade draws numerous parallels in experience and also uncovers intellectual links among them (334, 337, 338-39). For example, Virginia Woolf was rereading the works of Jane Ellen Harrison and Eileen Power as models for her never-to-be-completed revised history of English literature intended to include anonymous and forgotten women writers (29). [see also claims of direct influence through meeting in Cambridge (10, 169, 171) also H. D. 168] Another instance occurs after Dorothy L. Sayers and Eileen Power met at a party in Oxford in 1938. Power was able to send Sayers sources about Palestine under Roman rule which she needed for background of her play, He That Should Come (338-39).

It’s impossible to do justice to this book in a short review, because it excels in so many ways. Wade’s choice of iconic female role models is impeccable and the device of linking them through the setting of time and place in Mecklenburgh Square and Bloomsbury between the world wars is both functional and fascinating. Her prose style is graceful as she unspools the riches of her research in a compelling narrative. The enormous breadth and depth of Wade’s research are reflected in even a cursory browse through the Notes and Bibliography, which not only include information on her principal subjects, but also on other notable female residents who were reluctantly omitted. In addition, they reveal her keen dedication to her subject in her ingenious and inexhaustible search for sources.

Kólá Túbòsún. “The Library in September.”

One of the insights Wade gleaned from writing this book is how ‘knowledge of the past can fortify us in the present: how finding unexpected resonances of feeling and experience, across time and place, can extend a validating sense of solidarity’ (338).

Reading Square Haunting has certainly forged bonds of solidarity for me with these five extraordinary women who might have been my neighbours had I been born earlier.

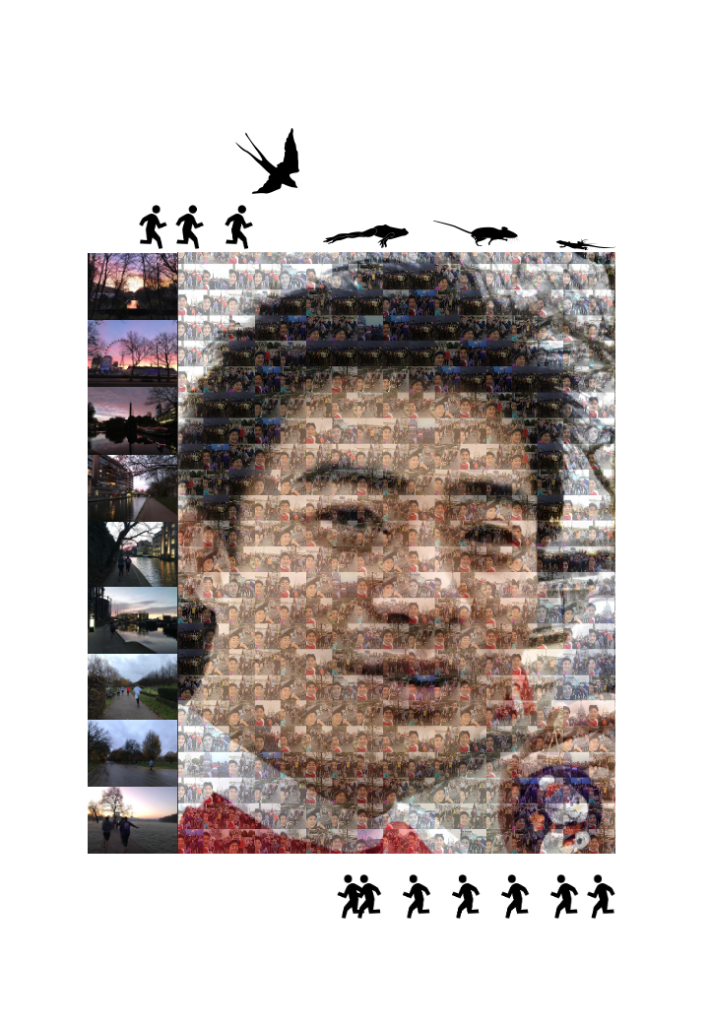

“Running Beyond the Square” – Goodenough Running Club 2019-2020

by Chi-Yu Lee

Fifteen Minutes by Foot

by Claire Hurley

Walking briskly Northwards in the autumn chill, that’s about how long it takes to reach the entrance of the Canal footpath tucked away behind the British Library. Or, heading West, fifteen minutes will take you past Senate House and into the warm glow of the hanging lights on Store Street, where there is a friend waiting, and good coffee, and coconut cake.

Regent’s Canal in November

Like any great city, London is meant to be discovered on foot. Living at Goodenough makes this pursuit almost too easy. So many worlds open up in your palm, dozens of landmarks and countless unremarkable sites charged with private meaning. I head out with no destination in mind, recalling my mother’s instruction to “always look up!” Sometimes staying within the College’s orbit, registering unexplored corners, alleys, storefronts. Sometimes pulled along by curiosity and the freedom of no plans until dinner. Forging a circuitous path the exact length of a podcast episode. On any given day, never enough eyes to account for all that is given to sight.

A body in motion comes to know the texture of a place. This is where you live. Did you ever imagine? The route to that favourite bookshop becomes familiar and takes on a particular hue. What does it sound like in the waning morning? How does it smell?

Secret Garden Beyond St. Pancras

There is so much ground yet to cover. I know it won’t be the same when I eventually get back to it, clinging to that old feeling. Looking for signposts or the shadow of prior footsteps on the grass. Mine, yours. But change is a universal maxim. And nothing is lost, only transformed. On a Tuesday in February, the trees and the stone stand firm in the secret garden. Quiet despite the urban din beyond the gate, hidden in plain view.